| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||||

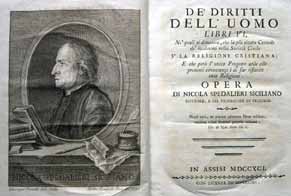

In 1779, on occasion of solemn celebrations for the recovery of the Governor and Pius VI, he kept two famous speeches in Rome about the "Arte di governare" (Governing Art) and the "Influenza della religione cristiana nella società civile" (Influence of the Christian Religion in Civil Society) in which he was already anticipating the themes of his most important work. In 1784 he wrote another mighty apologia of Christianity, the Gibbon Confutation, that, in his History, had attributed the decadence of the Roman empire to the Christianity. In his more important work "Dei diritti dell’uomo" (About the rights of man) (1791), the Spedalieri, moving from the thesis of the contract as origin of society, claimed that the Christian religion is "the safest keeper of man's rights" a guarantee against the abuse of despotism justifying the rebellion to the authority, when this does not respect "the natural rights" which had been somewhat dispensed with by the French revolution. His ideas (against the absolutism, on the sovereignty and on the right of the people to knock down the tyranny), very advanced for the time, in a moment of transition and of grave ideological tensions, sowed dismay in the absolutist courts and in the curial circles. The pontiff Pius VI allowed the publication of the book in Rome, even if with the false indication of Assisi and the frontispiece deprived of the ritual ecclesiastical approvals, replaced by the hastiest formula "with license of the superiors". The work had an extraordinary book success: in a brief while was reprinted four times and in various towns, as the first numerous exemplary were not sufficient to satisfy the requests coming from theologians, jurists, politicians and Italian and European men of culture. It provoked also much hatred and ferocious criticisms and a crusade of books and brochures tried, with poisonous insults, to confute and demolish the philosopher advanced theses. The Spedalieri had again to fight against the moderate lay, the religious and also the progressist thinkers (Rosmini, Taparelli-D’Azeglio, Cantù).

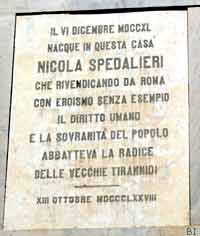

The doctrine "Of the rights of man", that was teaching the popular sovereignty and the recognition of the fundamental rights of man was considered dangerous and subversive; the Savoy House forbade in 1792 the spreading of the book in Italy. The work was also forbidden up to 1860 in all the kingdoms and the European courts of the epoch. The last book of the Spedalieri, "Storia delle paludi pontine" (History of the pontine marshes), written in Latino by wish of Pius VI, was translated into Italian, and published in 1800 after the death of the great philosopher. Nicola Spedalieri died suddenly in Rome on November 26th 1795. From this was born the legend of having been poisoned by one of his many opponents. He was buried in the San Michele Magno oratory, property of the Vatican Chapter. The papal state coined in his honor a medal and had a mosaic built in front of his grave (the epigraph says "Memoriae Nicolai Spedalieri presbiteri nazione siculi domo Bronte..." (Memoriae Nicolai Spedalieri siculi nation presbyteries subdue Bronte ...). In his twenty-one years of residence in Rome he established friendly relationships with the most illustrious prelates, scholars and artists of the time (the Cardinal Borromeo, Vincenzo Monti, Winckelmam, Milizia, Canova, Mengs and others). Nicola Spedalieri was interested also in music (he was an excellent harp player) and of painting that he loved and studied since the first years spent in Montreal. The Vatican library preserves the originals of a few of his musical works; his harpsichord (of 1679, attributable to Petrus Todinus), recently restored and his self-portrait (painted when he was thirty-three years old, in 1773) are preserved in the premises of the Capizzi College, together with other writings and objects of his (The Spedalieriane relics). A big Nicola Spedalieri statue ("La Nuova Italia a Nicola Spedalieri - MCMIII") was built in Rome very close to the Vatican (in Piazza Cesarini Sforza, on the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, in the New Church). The statue (the first of a Sicilian built in the Capital) was sculpted by the Sicilian Mario Rutelli, winner of the national contest kept in Rome in April of 1895. The Council of Bronte participated to the cost of the work with L. 1.000; Many contributions arrived also from other Councils of Sicily: Regalbuto (Lit 50), Niscemi (L. 30), Aidone (L. 10), Palermo (L.100) and her give her Province Of Catania (L. 1.000), Girgenti (L. 100), Caltanissetta (L. 200) and Palermo (L. 300). The State gave L. 4.000; King Umberto ("high admirer of the innovating doctrines of the Bronte's philosopher") contributed to the ejection of the monument with L. 500 (a century before, in 1792, the Savoy house had instead forbidden the spreading in Italy of the book "Of the rights of the man"). | ||||||||||||

Nicola Spedalieri (Bronte 12.6.1740 -- Rome 11.26.1795), great philosopher, was an author of the "De’ diritti dell’Uomo" (On the rights of man) with which he was the first in Italy to talk about the natural rights of man and proclaimed from Rome the sacredness of principles of equality and freedom.

Nicola Spedalieri (Bronte 12.6.1740 -- Rome 11.26.1795), great philosopher, was an author of the "De’ diritti dell’Uomo" (On the rights of man) with which he was the first in Italy to talk about the natural rights of man and proclaimed from Rome the sacredness of principles of equality and freedom. A legend tells that in the first days, dressed as Calabrian farmer, with leather shoes, velvet jacket, skin bodice and funnel hat, earned his living playing the harp in the squares and in front of the inns in the courtyards of the princely palaces.

A legend tells that in the first days, dressed as Calabrian farmer, with leather shoes, velvet jacket, skin bodice and funnel hat, earned his living playing the harp in the squares and in front of the inns in the courtyards of the princely palaces.

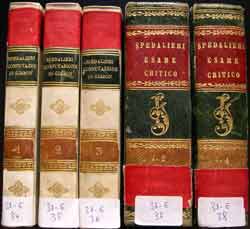

His first important philosophical work is of 1778 (four years after his coming to Rome): 472 pages, in 8° grand, in defense of religion and entitled "Analisi dell’Esame critico del cristianesimo di Nicola Frèret" (Analysis Of The Critical Exam of Christianity by Nicola Frèret). The work had a remarkable success and the name of the Spedalieri became very popular in Rome and in all Christendom.

His first important philosophical work is of 1778 (four years after his coming to Rome): 472 pages, in 8° grand, in defense of religion and entitled "Analisi dell’Esame critico del cristianesimo di Nicola Frèret" (Analysis Of The Critical Exam of Christianity by Nicola Frèret). The work had a remarkable success and the name of the Spedalieri became very popular in Rome and in all Christendom. Among the many detractors, also a fellow villager of his, the friar Capuchin

Among the many detractors, also a fellow villager of his, the friar Capuchin

Projects and sketches presented to the National Committee in the competitions for the erection of a Statue of the philosopher Nicola Spedalieri in Rome. The ones above are by the sculptor Mario Rutelli from Palermo. The commission of the first competition did not consider any of the 24 sketches presented worthy of execution. The sculptors Rutelli (photo on the right), A. Ghigli, Michele La Spina and Antonio Ugo participated in the second competition, among others.

Projects and sketches presented to the National Committee in the competitions for the erection of a Statue of the philosopher Nicola Spedalieri in Rome. The ones above are by the sculptor Mario Rutelli from Palermo. The commission of the first competition did not consider any of the 24 sketches presented worthy of execution. The sculptors Rutelli (photo on the right), A. Ghigli, Michele La Spina and Antonio Ugo participated in the second competition, among others.

On the right, the philosopher's self-portrait and the manifesto launched in 1896 by the National Committee for the erection of the statue on the 1st centenary of the death of Nicola Spedalieri (exhibited in Bronte, together with the sketches, in November 2005 on the occasion of a

On the right, the philosopher's self-portrait and the manifesto launched in 1896 by the National Committee for the erection of the statue on the 1st centenary of the death of Nicola Spedalieri (exhibited in Bronte, together with the sketches, in November 2005 on the occasion of a  On the left, the Self-portrait of Nicola Spedalieri, preserved in Bronte among the Spedalieriane Relics in the Real Collegio Capizzi. The painting was made at the age of 33.

On the left, the Self-portrait of Nicola Spedalieri, preserved in Bronte among the Spedalieriane Relics in the Real Collegio Capizzi. The painting was made at the age of 33. n the right, an unusual (we would say modern) and little-known image of the abbot Nicola Spedalieri taken from the tombstone that covers his modest tomb in Rome.

n the right, an unusual (we would say modern) and little-known image of the abbot Nicola Spedalieri taken from the tombstone that covers his modest tomb in Rome.

Another

small painting on a panel, in addition to the

self-portrait and the spinet, is attributed to Nicola

Spedalieri. The panel (which is the door of a

tabernacle) measures 15 cm. by 30 and is preserved in

Bronte in the church of SS. Trinità (the Matrice).

Another

small painting on a panel, in addition to the

self-portrait and the spinet, is attributed to Nicola

Spedalieri. The panel (which is the door of a

tabernacle) measures 15 cm. by 30 and is preserved in

Bronte in the church of SS. Trinità (the Matrice). The

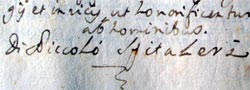

autograph signature of the Philosopher. We

have obtained it from the

The

autograph signature of the Philosopher. We

have obtained it from the

Pious VI

recognized and appreciated his merits, placed great

trust in him and wanted him close to him to have valid

help for the works he intended to entrust to him. With

the aim of keeping him in Rome and distracting him from

the university chair of Pavia that had been proposed to

him, he wanted to help him with a modest compensation (a

few dozen scudi a month) giving him the title of

beneficiary of the Vatican basilica and this in

opposition to a rule of Leo X, which forbade non-Roman

citizens to occupy such a post. He also entrusted him

with the task of writing a History of the Pontine

Marshes (published posthumously in 1800 by Monsignor

Nicolai with the title "De' Bonificamenti delle terre

pontine").

Pious VI

recognized and appreciated his merits, placed great

trust in him and wanted him close to him to have valid

help for the works he intended to entrust to him. With

the aim of keeping him in Rome and distracting him from

the university chair of Pavia that had been proposed to

him, he wanted to help him with a modest compensation (a

few dozen scudi a month) giving him the title of

beneficiary of the Vatican basilica and this in

opposition to a rule of Leo X, which forbade non-Roman

citizens to occupy such a post. He also entrusted him

with the task of writing a History of the Pontine

Marshes (published posthumously in 1800 by Monsignor

Nicolai with the title "De' Bonificamenti delle terre

pontine").