Bronte's History The eruption of 1843 The night of the 17th of November (by Benedetto Radice)  «At 9 o’clock P.M, on the 17th of November, after violent earth tremors, gloomy announcers, some fifteen mouths, close together, appeared as one only gorge opened up, on the back of Etna, West North West, on a site called Quaranazzi, about a kilometre above the 1832 eruption crater. «At 9 o’clock P.M, on the 17th of November, after violent earth tremors, gloomy announcers, some fifteen mouths, close together, appeared as one only gorge opened up, on the back of Etna, West North West, on a site called Quaranazzi, about a kilometre above the 1832 eruption crater.

Among continuous rumbling, isolated gorges, launched rocks of various size, to which followed explosions of slag and lapilli, when suddenly gushed a river of lava, as melted metal, that, going over the one of 1832 with a front of nearly 800 metres, in few hours covered a distance of over 3 km, and between mount Egitto and mount Rovere divided into tree branches. The one to the right was going towards Maletto, the left one towards Adernò, and the one in the middle, towards Bronte. The lateral branches soon started to slow down, while the centre one, swelled by the coming up lavas, first flanked Dagala Chiusa, and then, the ancient lavas of the precedent eruption.

Neither the rough, uneven surface of the 1832 one, nor that more ancient of mount Rovere could hold the rush of the red-hot lava, that advanced threatening towards Bronte. The people, stricken by fear and anxiety, were getting ready to abandon the town, when, just in time, arrived the “commendatore Giuseppe Parisi”, superintendent for Catania’s province, to comfort the prostrate people and put some order in that bustle of departures; however, this infernal river stopped at the Victory hillock, two miles from Bronte, and turning South, invaded the Paparia’s old lavas. Pressed by the coming up flood on the 23rd, was at Fiteni in Tripito district, and in few hours went across the consular road Palermo-Messina, with a front of about 400 meters and 7 to 12 metres high. Fear was in the mind of all the inhabitants who had come also from nearby towns to look at that horrible and marvellous spectacle. The lava on the 25th took the slope of the valley formed by the western layers of Etna to the left, and the Placa mounts to the right, destroying whatever it met all along the way. "Quivi sospiri pianti ed alti guai

risuonavano par l'aria..."

("Thereby sighs, cries and high whines

resounded in the air...")»

The night of the 25th of November

Women and children, genuflected, were praying the heavens. The men, some of them were cutting with an axe trees that could easily be engulfed in devourer flames; others were taking away roof tiles and doors from the rustic, small houses. Women and children, genuflected, were praying the heavens. The men, some of them were cutting with an axe trees that could easily be engulfed in devourer flames; others were taking away roof tiles and doors from the rustic, small houses.

The lava was flowing slowly towards the Dagala and Barrili districts, threatening factories, aqueducts and even the Simeto’s waters, when something more evil happened, after dinner, on the 25th, in the chemist Ignazio Zappia’s farm. Suddenly the lava started to swell and to rise, little by little, like a dome; then explode violently, crumble the compact igneous mass, rise the earth of the invaded soil, and spread all around a dense fog of smoke, full of red-hot lapillus, launched vehemently up in the air.

Many, like the damned of Sodoma and Gomorra, caught, beaten by that rain of fire, were burning, smoking like living torches; running, shaking, writhing , wrinkling like fire touched leaves and slumping to the ground.

Sixty one persons from Bronte, from a distance of about sixty metres, fell down, some of them dead, some nearly dead, some wounded.

The reason of such horrible and pitiful happening was a spring of water at the Barrili’s fountain, that, covered by the red-hot lava, evaporating quickly, raised up like a column and poured down, in cinders, over the wretched people below. As the terrible news reached Bronte. The people run to Our Lady’s church, asking for mercy; in procession they took the statue to Scialandro, opposite the flaming Etna, to placate the fury of the inexorable volcano. While everyone was crying, suddenly, under a gloomy sky (too horrible even to imagine it!), appeared some naked men, scorched, black, greenish, bleeding, carried on the shoulders by crying and desolated men. Were they coming from hell? They were the victims sacrificed to the fury of the Vulcan god; a scene worth of Dante’s pen, of the Goya and Salvatore Rosa’s brushes. On the 26th the lava was slowing down; on the 27th the volcano’s mouths stopped erupting; on the 28th were extinct. The invaded surface, in the West North West side of Etna, was about six miles long, half a mile wide and from six to twelve metres high.»

On the same episode and about the disaster of the November, 1843, we report a page written by Giuseppe Cimbali in his book “Terra di Fuoco – Leggende siciliane” (Land of Fire - Sicilian legends) Euseo Molino Editore, Roma 1887.

The style is certainly not historic, like the Radice’s one, but the events description leaves anyone impressed and distraught by the devastating power of our beautiful “Muntagna”. The legend title is “la Madonna dell’Annunziata”.

And the lava was flowing, flowing non-stop

(by Giuseppe Cimbali)  «[…] A dense fog, like a mantel of bronze, covered everything, sky and land. In the heavy and oppressing air hovered such a hot and inflammable filminess that the minimum rubbing, a slight spark, could have started a universal fire. «[…] A dense fog, like a mantel of bronze, covered everything, sky and land. In the heavy and oppressing air hovered such a hot and inflammable filminess that the minimum rubbing, a slight spark, could have started a universal fire.

Everywhere a nauseating and caustic odour of fused metals that was burning the eyes, slapping the face, oppressing the lungs; it was hard to breathe. It was a never seen spectacle, that generated fear. Could have been the prelude of a solar eclipse, maybe of a thunderstorm, maybe of an earthquake, maybe of an Etna’s eruption.

Confused and unceasing murmurs were raising from any part of the town and, being joined together high above, took the shape of an anguished lament. At any moment one could be transported, in the coils of a cyclone, hundreds of miles away; at any moment one could be swallowed by the gashed earth’s womb; at any moment one could be buried under a rain of red-hot sand! Then, suddenly the scene changed, becoming more dreadful. Some stunning booms, rumbling continuously and causing terrifying echoes everywhere. where shaking houses, mounts, the ground itself like a tree leaf, and, it looked like they wanted to overwhelm the entire universe, enlivened, more sombrely, the silence of the mute, impending darkness. Later, the cannonade, having reached the parabola’s top, started to decrease and, in the direction of those booms, spurted suddenly a source of colossal light, whose flames, with irrepressible leap, broke down the third sky.

The surrounding gloomy filminess acquired straight away the colour of the reddish reflections, and everything appeared engulfed in the flames of a final destructive fire. The worry then became fear, and the words of surprise became shrieking with terror. An interminable cry burst out, quivering from everybody’s hearth. They were lost: and, in the imminence of the definite danger, there was a fervent praying, a disdainful cursing, a turbulent abandoning of the houses, a crazy ringing the warning bells, a hasty running into the churches, as a last refuge, a reciprocal calling and calling desperately, an furious embracing and kissing as for the last farewell. They were lost: lost without any hope of salvation! Later, unexpectedly, the rumbling stopped completely and the fog started to clear away from part of the horizon, allowing to see daylight and putting a soothing reassurance on most people. The dense darkness had retreated, hand by hand, around mount Etna, lost in a sea of stormy smokiness, from whose sides, lacerated in many parts, descended ravaging a spreading river of fire. The eruption lasted many days, with the same violence. Bronte, however, like in previous eruptions, was not in any danger. Oh yes, there was, there had been and there always be the Good Genie that watches over the blessed Cyclopean land to be protected by the desolation, so that could produce the vigorous claimant of human rights and of the new power of italic young people! Often the lava has come very close to it, threatening, with the spectre of its ruins, but in vain, has always had to swallow up again its destructive greediness. Out of spite has often claimed victory by drying up the fertile fields nearby, changing them from flourishing gardens to immense deserts of enormous and blackish rocks, accessible only to the solitary broom that, at springtime spreads the grateful odour of its yellow and velvety flowers, among so much ungrateful squalor; but the heart remained always intact; and that heart glows even in the middle of the desert; is fruitful even among the devastation, wins over all and triumphs.  That’s that: all the spites were not over; on the slopes of Etna remained yet some fertile grounds to be destroyed in order to complete the general ruin; and are exactly these grounds that are now being covered by immense incandescent masses, which, when cooled down, shall seal for untold centuries its sterility. They made a strange contrast, indeed. That’s that: all the spites were not over; on the slopes of Etna remained yet some fertile grounds to be destroyed in order to complete the general ruin; and are exactly these grounds that are now being covered by immense incandescent masses, which, when cooled down, shall seal for untold centuries its sterility. They made a strange contrast, indeed.

On one side the desert and on the other the enchantment of a marvellous tropical vegetation! It had to equalise all into nothing, then. And the lava at this was working, working non-stop. One day, when the hearts were already reassured and the pain for the losses was reduced, as the people thought to be safe and sound, a dreadful boom was heard, like the explosion of a very strong force, compressed for a long time, that resounded all over Sicily, as if wanted to shatter it.r> The sky was suddenly covered by a hot and very dense fog, the sun was sinisterly eclipsed and, flying in the air, somebody saw human limbs and entire bodies that dispersed into smoke, soon afterwards.

The town was again in great confusion; and the confusion became frenzy when, soon afterwards, the news were out. The lava had been jealous of its destruction work: jealous to the bitter end. Many persons, that day, were trying to eradicate young and healthy trees, which would be surely run over by the invading extermination, to transplant them in less unfortunate areas. For this rescue work they thought to gain the gratitude of the great vegetable family and were happy to save from certain death many beings worth living and producing fruit again. The lava, being jealous, appeared to be stopping; but was swelling, swelled like swells in an hostile heart an irrepressible hatred to hit harder afterwards, exploding suddenly. Those poor fellows thought that the lava was agreeable with their good work and apparently had paused its flow to give them more time for their work; and they, unmindful of the impending danger, became bolder and more active. In the moment of their major recklessness, however, the treacherous bubble exploded and the victims could not be counted! At once the town, as a single body, run to the disaster’s area with tears of desperation, with horrifying groans, that made tremble the nature around, calling aloud the name of the father, or of the brother, or of the friend, or of the husband, or of the lover. To many did not answer anybody; to others, maybe more unhappy, answered only a faint human voice that was disgusting, coming from men changed in horrible, infernal monsters. Most, in fact, had completely disappeared in the disaster, without leaving any trace, and the others were like pieces of wood reduced to charcoal, putrefied and animated only by a fleeting breath of life. The bell of the Last Sacraments, that was coming to give the last comfort to the dying, which mostly passed away dissolving before reaching the town, spreading the hope of an eternal, better after life, out of this world, was interrupting, from time to time, the endless crying of the people that sounded sadder in the bondless horizon of the desolated country. - The Virgin Mary therefore had forgotten her beloved sons to allow so much torture? B ronte, then, more than the received misfortune, was afraid to be abandoned by its patron saint. Without her couldn’t have to whom to appeal in case of disasters. ronte, then, more than the received misfortune, was afraid to be abandoned by its patron saint. Without her couldn’t have to whom to appeal in case of disasters.

Abandoned to itself, couldn’t have any more a day, a single day of life. Because only the beautiful Virgin Mary had wanted to be its patron saint, its mother, and only she could save it in the future as had done in the past, from the blind fury of the volcano (Mongibello). When, the day after, all the people run to the church to pray the Great Lady to have pity on them and save them from other disasters and other victims, they found the marvellous marble statue with two large tears trembling in her eyes and with some sweat on her forehead. Oh no: she had not forgotten her beloved sons! It meant that those victims were necessary and, although she had tried hard to intercede, she could have not obtained the requested grace, from God’s mercy, in times of so much corruption.

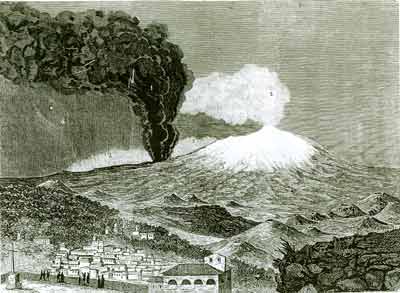

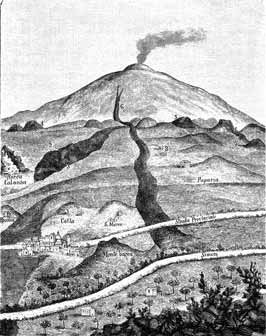

The people wanted its celestial mother to be taken down from her altar: they wanted her in the middle of the church. This way they could pray her more warmly, and she would certainly answer their fervent prayer. Then, they took her outside in procession and placed her facing Mongibello (the volcano), still horribly threatening. Soon after, the miracle was done. The eruption appeared extinct since one hundred years.» In the photos: a vision of the City of Bronte lying at the foot of Mount Etna; a spectacular explosive activity of the volcano with a high ash cloud that hangs over Bronte (the photo was taken a few years ago); a drawing of 1882 with «The eruption of Etna, seen near Bronte»; another drawing of the eruption of 1843, taken from the book by De Luca and Monte Nunziata, formed for the eruption of 1843.

|